With a 2023 pre-commercial deployment target in mind, HAPSMobile Board Member Ryuji Wakikawa discussed the potential of the SoftBank subsidiary’s Sunglider project in an exclusive interview with 6GWorldTM.

Comparing HAPSMobile and Loon

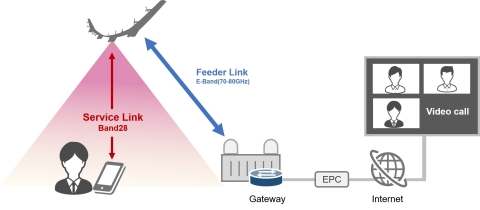

Constructed as an airborne base station, the solar-powered Sunglider is an unmanned aircraft whose payload depends on the technology currently available. So, while the Tokyo-based HAPSMobile and Alphabet’s Loon recently made the world’s first successful delivery of LTE connectivity from a fixed-wing High-Altitude Platform Station (HAPS), 5G is still a possibility at some point.

“Once the equipment is available, we can easily deploy 5G from the HAPS,” said Wakikawa, who also serves as VP of SoftBank’s Advanced Technology division. “Where you see handset penetrations, only a few percent of [them are] 5G mobile phones. For example, if the deployment [of 5G is widespread] in five years, of course 5G must be an option.”

Of note, Loon recently shut down operations due to a lack of a commercially viable business plan. Wakikawa expressed his disappointment when asked about the news. He nevertheless believes HAPS remain a worthwhile infrastructure avenue for SoftBank to pursue.

“We lost a partner, but we don’t have any plan to slow down this journey by ourselves. I don’t think there’s significant damage on our path. However, community-wise, there might be a negative message, how Alphabet gave up on HAPS, but Loon and HAPSMobile are two totally different solutions, I believe. There may be some influence in the future, but we can probably figure out how we can travel by ourselves,” he said.

Of note, as Wakikawa alluded to, HAPSMobile’s Sunglider aircraft is a drastically different HAPS solution from Loon’s high-altitude balloons. While more affordable to deploy, balloons have their drawbacks. For example, balloons have to be replaced relatively frequently, according to Marco Giordani of the University of Padova’s Department of Information Engineering, who spoke to 6GWorld in an earlier interview about HAPS.

“They stay there usually for a few months. It would be better if they could stay there longer, to reduce the cost of deployment and also for the management of the connectivity,” Giordani had said.

In contrast, the Sunglider’s current design enables it to stay in the air for around six months. Wakikawa said that was just for now, though. It all depends on the battery. With an extended battery charging cycle, it could remain deployed in the stratosphere much longer.

HAPS on the Horizon

Ironically though, the more complex design of Sunglider works against it in some respects, higher cost excluded. There’s the need to accommodate strict regulations, something Loon didn’t necessarily have to worry about to such a great extent.

“One of the beauties of Loon is they are floating objects,” said Wakikawa. “Balloons cannot be regulated. That’s why they can provide service in Africa, because there’s no way to limit the balloons in the stratosphere[…] but airplanes are different. Airplane operation is regulated. So we need to create these regulations. This is why Loon was active earlier than HAPSMobile.”

Wakikawa argued that, as a result, regulations are the biggest obstacle facing the HAPS Alliance today, a consortium co-founded by HAPSMobile and Loon. Using LTE connectivity as an example, Wakikawa said that spectrum is standardised for use in base stations on the ground, not in the air.

“So, we propose defining the spectrum that can be used in the stratosphere in the ITU [International Telecommunication Union] and the ITU, every four years, has a standardisation meeting. We successfully registered ‘spectrum in the stratosphere’ on the agenda two years ago and the next meeting is 2023. That’s the timing to try to get approval,” Wakikawa said.

Hence the reasoning behind the projected 2023 deployment target. However, it’s not just the ITU with which HAPSMobile has to deal. For example, the Federal Aviation Administration is another regulatory body that enters into the equation, as Sunglider itself needs to be certified as an aircraft.

“Today our aircraft isn’t certified, because there’s no way to certify these types of bigger drones. We are working on that. [There are] also, operational regulations[…] like how to fly in the stratosphere. So, these two regulation activities are very, very important for commercialisation,” he said.

Nevertheless, Wakikawa remains confident HAPSMobile’s vision, which originated out of a need for natural-disaster-proof networks, will be realised. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident of 2011 actually sparked the idea for SoftBank to start developing HAPS, according to Wakikawa. A decade later, after many breakthroughs already, HAPSMobile believes it’s incredibly close. In Wakikawa’s mind, regulations remain the main issue. The technology isn’t an obstacle at all.

“Technology-wise, we’ve proved it works,” he said.

Feature image courtesy of HAPSMobile.